Parents experience larger gender employment gap

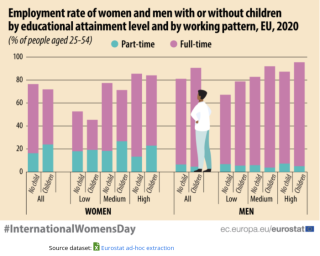

In the week that marks International Women's Day, figures from Eurostat show that across the EU, in 2020, having children in a household negatively affects the rates of employment for women. For men, the opposite is the case. In the EU, in 2020, 77 per cent of women aged between 25 and 54 without children were employed. Contrast this with the 72 per cent employment rate for women in the same age brackets who have children, a drop of 5 percentage points.

Conversely for men, having children in the household saw more men in employment with rates at 91 per cent compared to 81 per cent of men in households with no children, a drop of 10 percentage points.

Having children in the household also influenced the hours being worked. 24 per cent of women with children worked part time compared to only 16 per cent of women without children. Again, men experienced the opposite. 7 per cent of men without children worked part time compared to 5 per cent of men with children.

Eurostat notes that the levels of education attained by parents influenced the employment gap with the difference in the rates of employment for both men and women falling with higher levels of education. Women with a high level of education had the smallest gap between the rates with 86 per cent of women working without children compared to 84 per cent with. This gap increases as education levels drop. Women with mid level educational attainment had a wider gap between 77 per cent of women without children compared 71 per cent for women with children. The largest gap then was between women with low levels of education, 45 per cent with compared to 53 per cent without.

Women in the Irish workforce

Irish women are now better educated than their male peers, so a policy framework that diminishes their long-term participation in the labour force, or indeed excludes them from it altogether, is detrimental to the economy. An expansion of paternity leave and a reconceptualisation of the role of men in child-rearing would have many benefits, including:

- Reducing the extent to which salary and career progression opportunities are foregone by women. This would potentially reduce instances of women feeling that, given their diminished prospects as a result of leave taken, it may not be worth their while returning to employment;

- Changing employer attitudes towards potential parents. Gender discrimination at work is illegal but some employers may still avoid hiring women they believe are likely to take multiple periods of maternity leave in the short to medium term. At a very basic level, discrimination in the hiring and promotion process will be greatly reduced if employers believe that there is likely to be a less significant difference in the parental leave that male and female candidates are likely to take.

- Reducing the instance of women returning to the workplace after an extended period away to find their skills are outdated.

Time-use studies show that even when both parents work the same amount outside of the home, the woman usually bears a larger share of the housework and childcare responsibilities. More hands-on fathering would help share this burden more evenly, and reduce the extent to which many women must instead work part-time or in jobs for which they are overqualified.

Social Justice Ireland has long advocated the recognition of all work, including work done in the home; work done by voluntary carers and work done by volunteers in the community and voluntary sector. We have also encouraged the implementation of policies that would narrow the gender pay gap and increase the participation of women in the Irish labour force. We believe that paternity leave should be expanded and call for real investment in Ireland’s childcare infrastructure.

Paternity Leave

The dual benefits – economic and social – of encouraging more women to join the workforce whilst simultaneously allowing working mothers to spend time with their children are no longer debated. Most countries (of 185 countries surveyed by the International Labour Organisation, only the United States and Papua New Guinea do not have paid maternity leave as standard) have paid maternity leave, but many of these countries have failed to expand this initiative. Studies indicate that the gains from paid maternity leave would be multiplied if countries extended paternity leave for new fathers too.

Childcare

Childcare costs in Ireland as a percentage of income are by some measures the second highest in the OECD. In many instances, the high cost of childcare makes it economically unviable for women to return to the workplace. A report from the ESRI showed that all else being equal, mothers with higher childcare costs at age three tended to work fewer hours when their child was aged five. It should be the aim of government to develop an affordable childcare network that will remove the necessity for people, mainly women, to make the choice between staying at home and returning to the workforce on a purely financial basis. It is time to start investing in this area and moving Ireland's childcare infrastructure in the direction of the European norm.