European Year of Youth 2022

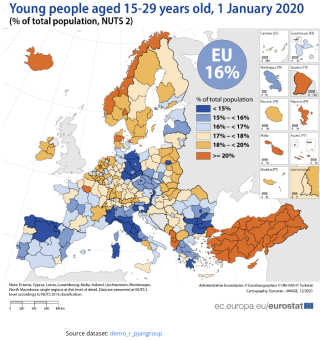

To mark 2022 being the European Year of Youth, Eurostat published the proportion of young people at regional level in the EU. As of the 1st January 2020, 73.6 million people or one out of every 6 people was aged between 15 and 29 years old. 51 per cent (37.8 million) were young men and 49 per cent (35.8 million) were young women. In Ireland, there were 919,301 people between the ages of 15 and 29 years of age, equating to 18.5 per cent of the overall population.

There was an almost even split between three age categories:

Aged 15-19 – 323,325

Aged 20-24 – 305,817

Aged 25-29 – 290,159

The European Commission is making a commitment to the youth of Europe by acknowledging that it “needs the vision, engagement and participation of all young people to build a better future, that is greener, more inclusive and digital….Europe is striving to give young people more and better opportunities for the future.”1 and by working side by side with the European Parliament, authorities across all Member States and the young people themselves aims to:

“to honour and support the generation that has sacrificed the most during the pandemic, giving them new hopes, strength and confidence in the future by highlighting how the green and digital transitions offer renewed perspectives and opportunities;

to encourage all young people, especially those with fewer opportunities, from disadvantaged backgrounds, from rural or remote areas, or belonging to vulnerable groups, to become active citizens and actors of positive change;

to promote opportunities provided by EU policies for young people to support their personal, social and professional development. The European Year of Youth will go hand in hand with the successful implementation of NextGenerationEU in providing quality jobs, education and training opportunities; and

to draw inspiration from the actions, vision and insights of young people to further strengthen and invigorate the common EU project, building upon the Conference on the Future of Eu”2

Youth and Employment

It is clear that young people face a particularly challenging labour market situation. The European Commission is proposing that a minimum of €22 billion be mobilised for a Youth Employment Support package to mitigate the effects of the coronavirus pandemic for young people in the labour market and the impact of a digital and green transition. The Irish Government should use the strands of the Youth Employment Support Package as a guide to designing a strategy to deal with this crisis at a national level taking into account the learning from the Irish experience of implementing the Youth Guarantee after the financial crash of 2008 and the findings review of the revised Apprenticeship Scheme.

Youth and Housing

Housing for All, the Government’s current housing strategy commits to the launch of a Youth Homelessness Strategy by early 2022. There are many barriers that can be faced by young people in accessing accommodation. Firstly, they are in receipt of reduced welfare rates. At the time of writing, a job seeker claimant aged between 18 and 24 will receive a maximum rate of €117.70 per week.

Secondly, even when in full employment, wages can be low at a time when rents are high. According to a report by FEANTSA, the European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless, “In Ireland, average rent in the second quarter of 2020 was EUR 1,256 nationally, and EUR 1,758 in Dublin, against an average income of EUR 1,176 for young people aged 15-24”. Lastly, by virtue of being younger, they will be much lower down the social housing list if they are eligible and may struggle to afford single bed accommodation in the private rental sector even with social housing supports.

Much has been written about the impact of the Covid 19 pandemic restrictions on the job prospects of the young. This in turn impacts on their ability to pay their rent which may result in either homelessness or back living temporarily with friends or family. The focus during the post Covid period must also take into account housing for the young as well as retraining and reskilling opportunities. Lack of security in both work and accommodation can cause disruption to concentration and learning and impacts on the support networks young people need which are important for mental and physical health. The new Youth Homelessness Strategy must ensure that vulnerable young people do not enter adulthood whilst homeless.

Youth and Education

It is recognised that better educational levels help employability, which in turn will help to reduce poverty. A report published by the Central Statistics Office showed that Ireland ranked second in the EU for the percentage of people aged 20-24 with at least upper-second level education at 94 per cent. However, for those who leave school early, the impact of that will have both individual and societal and economic consequences. A review of the economic costs of early school leaving across Europe confirms that there are major costs to individuals, families, States and societies. That study showed that inadequate education can lead to large public and social costs in the form of lower income and economic growth, reduced tax revenues and higher costs of public services related, for example, to healthcare, criminal justice and social benefit payments.

According to the CSO, an early school leaver is three times more likely to be unemployed than the general population aged 18-24. Only one in four of them are in employment compared to the general population for that age group and just under half (47 per cent) are not economically active.

Ireland’s early school leaving rate must also be viewed in light of the country’s NEET rates (young people neither in education, employment nor training). Ireland’s NEET rate has increased for those aged 15-24 from 10.1 per cent in both 2018 and 2019 to 12 per cent in 2020.3Ireland still faces challenges in the area of early school leaving and young people not engaged in employment, education or training (NEETs), especially in disadvantaged areas.

Youth and Health

The Growing Up in Ireland study highlights a widening health and social gap that begins for young people by the time they are just 5 years old. Children from the highest social class (professional/managerial) are more likely than those from the lowest socio-economic group to be considered very healthy and have no problems. Another study from the Growing Up in Ireland series shows that economic vulnerability, particularly persistent economic vulnerability, has negative consequences for the socio-emotional development of children. So that reinforces the need for a policy focus on child poverty and deprivation to address child health. Obviously, children’s wellbeing is still very much shaped by their parents circumstances and social position, which results in persistent inequalities despite improvements in health, education and other areas in Ireland over time. Appropriate supports must be targeted early on to lessen the impact as these children become young adults.

According to the latest available data, the HSE Management Data Report for March 2021, 2,625 children and young people were awaiting supports from the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS). Of these one in ten were waiting for treatment for 12 months or more. A mental health crisis is likely to be a prevailing legacy from Covid-19, not just because of the immediate stress; but also the impact of the illness on those who contract it and their wider circle and on those who live in vulnerable households.4

Recognising the unique challenges faced by Ireland's young people as we transition through a global pandemic and the economic and societal fallout is the first step to ensuring that they receive the support and encouragement they need to lead us towards a fairer future.

1 https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_5226

2 Ibid

3 http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do

4 http://imj.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Impact-of-Covid-19-on-Mental-H…